‘First published on Lexology’

By: Pravin Anand, Vaishali R Mittal and Siddhant Chamola

A. INTRODUCTION

Standards‑essential patents (“SEPs”) protect technologies that are mandatory in a standard. The “essentiality” of these patents means that companies that manufacture products complying with a particular standard (such as 5G cell phones, or Wi-Fi6 routers) inevitably use these patents. To enable free and fair commerce, Standard Setting Organizations (SSOs) require SEP owners to commit that they will offer licenses to their SEPs to all such manufacturing companies (“implementers”). The license must be offered on fair, reasonable and non‑discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

The way this works in practice is that SEP holders and implementers negotiate with each other to agree on what royalty terms are FRAND. Often, the disagreement between the two is about the amount of license fee that an implementer must pay to the SEP holder. When the disagreement persists, negotiations often break down.

When that happens, SEP owners may seek injunctions to stop infringing products, and implementers ask courts to set FRAND terms. Because patents are national, disputes play out in multiple countries at once.

An increasingly common scenario that has played out over time is that SEP owner enforces its patents in countries such as India, Germany, U.K, U.S.A, Brazil and now the UPC. Often, the SEP holder asks the court in one of these regions to set a worldwide FRAND rate that the implementer must pay for a license to its portfolio of SEPs. It may also seek a declaration from the court in one or more of these countries that the royalties proposed by it as part of its offers to the implementer, are FRAND.

In response, the implementer either agrees to have the FRAND rate set by the court that the SEP holder approached, or it files its a FRAND rate setting case before a court of its choice. Recently, implementers have turned to the UK or to China to file rate-setting actions.

This state of play with multiple courts risks conflicting views, especially on whether it is prudent to have different courts look at FRAND aspects of the same notional license agreement at the same time. This conflict is borne out by the recent string of interim license declarations granted by the UK Courts, and the very recent anti-interim license injunctions by the courts in Germany and UPC.

B. INTERIM LICENCES IN THE UK

What are they?

An interim licence is a declaration by a UK court that, pending a final FRAND ruling, a willing SEP owner would grant the implementer a provisional licence on specified terms. It is not an executed contract; rather, it signals that a licensor acting in good faith must offer a temporary licence. The remedy first appeared in Panasonic v. Xiaomi[1], where the UK Court of Appeal held that, because the parties had both given undertakings to be bound by the UK’s eventual FRAND decision, Panasonic’s pursuit of injunctions elsewhere breached its duty of good faith and a willing licensor would agree to enter into an interim licence[2]. The court reasoned that the declaration could nudge Panasonic to comply, even if it was initially reluctant.

The UK Court of Appeal extended this doctrine in Lenovo v. Ericsson[3]. In this case, it was Lenovo (implementer) that had filed a rate-setting action in the UK, while Ericsson (SEP holder) had filed a suit for injunction and rate-setting in the courts of the USA, and had undertaken to be bound by the FRAND terms set by the US Court, and not the UK Court.

The UK Court of Appeal found Ericsson’s injunction suits in the U.S. and refusal to submit to the UK FRAND rate setting case to be a sign of an unwilling licensor because according to the court (amongst other things) Ericsson was trying to extract terms more favourable to it than what the UK Court would determine as FRAND. The Court also found Ericsson’s strategy of wanting to leverage the power of national injunctions, to negotiate “supra-FRAND rates”. [4]

Similarly, in Samsung v. ZTE, the first instance UK High Court granted Samsung a declaration that it is entitled to an interim licence. The judgment criticised ZTE for filing “wave of unnecessary injunctive proceedings” for infringement of its SEPs in countries abroad.[5]

Why grant them?

As articulated in the Court of Appeal’s decision in Alcatel v. Amazon, the UK Courts view interim licences as a way to “hold the ring” during litigation, and prevent SEP owners from leveraging injunctions abroad to negotiate higher royalties, whilst ensuring that implementers pay something (rather than nothing) on an interim basis.[6]

Recognizing that an interim license is not as detailed as a FRAND analysis, UK Courts have declared that interim royalties should be the midpoint between the parties’ offers[7], and that this can be adjusted against the payments to be made after the FRAND trial and final judgment.

The treatment of comity

The Court emphasised that the declaration does not offend comity: if the SEP holder accepts, it reduces duplicate litigation; if it refuses, other courts remain free to proceed with their respective cases.[8] Thus, these decisions differentiate an interim license from an anti-suit-injunction. [9]

C. GERMANY PUSHES BACK: ANTI‑INTERIM‑LICENCE INJUNCTIONS

The InterDigital v. Amazon orders

In the last week of September 2025, the Munich Regional Court and the Manheim division of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) responded with unprecedented anti‑interim‑licence injunctions (AILIs), which were granted to InterDigital on an ex parte basis against Amazon. These orders were passed pursuant to Amazon having approached the UK High Court for FRAND-rate setting and an interim license with InterDigital. Through separate AILIs, the Munich court and the UPC ordered Amazon to withdraw its claim for an interim license for InterDigital’s patents in Germany and the UPC. The non-compliance of the AILI may invite daily costs against Amazon[10].

What stands out is that the courts issued the injunctions even before any infringement suit had been filed in Germany, viewing Amazon’s stated intention to seek UK relief as an imminent threat to their jurisdiction[11].

Reasons and comity

The publicly available version of the UPC decision found that an interim license (even if a declaration and not a license itself), can deter SEP owners into forgoing their right to enforce patents in UPC and therefore violates the SEP holder’s right to enforce its patents, and that deterrence even if not as strong as a coercion is sufficient to grant an AILI[12]. The court recognizes that interim license declarations encroach on constitutionally granted rights in EU member states.[13]

On comity, the UPC disagreed with the UK Court’s that because interim licenses save the courts in other countries a lot of unnecessary work, they do not violate comity.

The UPC noted that while the initial case (Panasonic v. Xiaomi) saw an interim license from the UK, because both the SEP holder and the implementer undertook to be bound by the FRAND rates that would be set by the UK Court, this condition seemed to have been dispensed with in more recent cases.[14]

The grant of AILI was justified by the Court as it was only a defensive action, meant to preserve the ability of an SEP holder to enforce its patents (in Germany and) EU member states, and that this AILI did not interfere with the jurisdiction of the UK Court in any manner.[15] The Court explicitly noted that the UK Court was free to decide the FRAND rate between the parties and also to decide the consequences if a party fails to comply with UK court orders.[16]

Finally, the court noted that if the parties’ differences saw parallel FRAND determination in different jurisdictions, then this must be accepted as the parties’ decision, but that there is “no room for economic considerations by a court in the best interest of parties, without mutual consent”.[17]

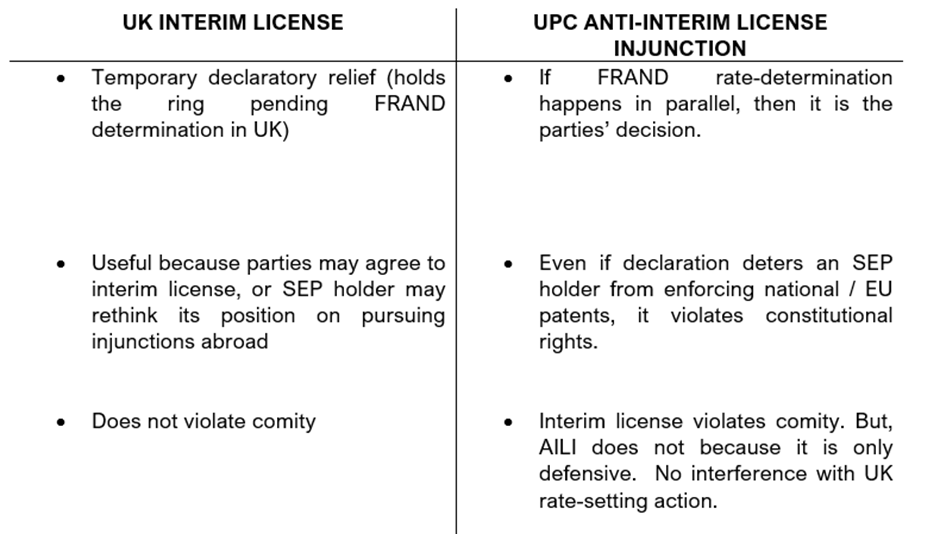

D. INTERIM LICENSES v. AILIs

E. INDIA’S PERSPECTIVE: SOVEREIGNTY OVER COMITY

India has not faced interim licence declarations, but it has confronted cross‑border injunctions. In InterDigital v. Xiaomi[18], the Wuhan Intermediate Court (China) passed an anti-suit-injunction (ASI) and ordered InterDigital to suspend its Indian patent suit. InterDigital sought an anti‑anti‑suit (anti‑enforcement) injunction (AASI) from the Delhi High Court.

The Delhi High Court granted relief, stressing that patents are territorial and Indian courts have exclusive jurisdiction over Indian patents. Further, the ASI order of the Wuhan court was found oppressive and contrary to natural justice. The AASI order restrained Xiaomi from enforcing the foreign injunction and required it to indemnify InterDigital for any penalties imposed against it in China.

Crucially, the court held that comity cannot override justice when a foreign order interferes with the Indian court’s sovereign authority. The Court also held that the AASI did not violate comity as there was no interference ordered by the Indian court against the proceedings in Wuhan.

The reasons backing the AASI order in India and the recent AILI order in UPC and Germany are very similar.

F. CONCLUSION

Interim licences have made the UK a magnet for implementers. The German court and UPC have fired their first salvo against interim licenses, and the stage is heating up. As SEP disputes proliferate, these conflicting approaches illustrate a fragmented global landscape

In the Indian context, the InterDigital v. Xiaomi AASI suggests how India might react to a UK interim licence, particularly if it agrees that an interim license deters an SEP holder from enforcing its patents in India. However, it remains to be seen whether an Indian court will view the declaration of an interim license (as opposed to its enforcement) as oppression enough to warrant an injunction. Based on India’s general temperament of non-interference and high deference to comity, Indian courts are likely to adjudicate FRAND and infringement issues independently of foreign declarations.

Whether courts can harmonise their methods or whether jurisdictional competition will intensify remains to be seen. What is clear is that the global stage is heating up, and the issue is far from settled. Unless it is, SEP enforcement strategies worldwide will remain nebulous and will change rapidly.

To view all formatting for this article (eg, tables, footnotes), please access the original here.

etc. whilst wrongfully claiming to be part of our firm and making false claims and allegations.

etc. whilst wrongfully claiming to be part of our firm and making false claims and allegations.